- Home

- Raymond Antrobus

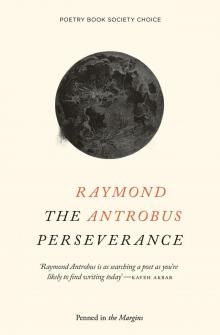

The Perseverance

The Perseverance Read online

THE PERSEVERANCE

Raymond Antrobus was born in Hackney, London to an English mother and Jamaican father. He is the recipient of fellowships from Cave Canem, Complete Works III and Jerwood Compton Poetry. He is one of the world’s first recipients of an MA in Spoken Word Education from Goldsmiths, University of London. Raymond is a founding member of Chill Pill and the Keats House Poets Forum. He has had multiple residencies in deaf and hearing schools around London, as well as Pupil Referral Units. In 2018 he was awarded the Geoffrey Dearmer Award by the Poetry Society (judged by Ocean Vuong). Raymond currently lives in London and spends most his time working nationally and internationally as a freelance poet and teacher.

ALSO BY RAYMOND ANTROBUS

POETRY PAMPHLETS

To Sweeten Bitter (Out-Spoken Press, 2017)

Shapes & Disfigurements Of Raymond Antrobus

(Burning Eye Books, 2012)

PUBLISHED BY PENNED IN THE MARGINS

Toynbee Studios, 28 Commercial Street, London E1 6AB

www.pennedinthemargins.co.uk

All rights reserved

© Raymond Antrobus 2018

The right of Raymond Antrobus to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Penned in the Margins.

First published 2018

Printed in the United Kingdom by TJ International

ISBN: 978-1-908058-5-22

ePub ISBN: 978-1-908058-6-69

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

CONTENTS

Echo

Aunt Beryl Meets Castro

My Mother Remembers

Jamaican British

Ode to My Hair

The Perseverance

I Move Through London like a Hotep

Sound Machine

Dear Hearing World

‘Deaf School’ by Ted Hughes

After Reading ‘Deaf School’ by the Mississippi River

For Jesula Gelin, Vanessa Previl and Monique Vincent

Conversation with the Art Teacher (a Translation Attempt)

The Ghost of Laura Bridgeman Warns Helen Keller About Fame

The Mechanism of Speech

Doctor Marigold Re-evaluated

The Shame of Mable Gardiner Hubbards

Two Guns in the Sky for Daniel Harris

To Sweeten Bitter

I Want the Confidence of

After Being Called a Fucking Foreigner in London Fields

Closure

Maybe I Could Love a Man

Samantha

Thinking of Dad’s Dick

Miami Airport

His Heart

Dementia

Happy Birthday Moon

NOTES

FURTHER READING

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the editors at the following publications, where some of these poems were published previously, often in earlier versions: POETRY, Poetry Review, The Deaf Poets Society, Magma, The Rialto, Wildness, Modern Poetry in Translation, Ten: Poets of the New Generation (Bloodaxe Books), The Mighty Stream, Filigree, Stairs and Whispers, And Other Poems, International Literature Showcase, New Statesman.

I am grateful for support from Arts Council England, Sarah Sanders and Sharmilla Beezmohun at Speaking Volumes, Jerwood Compton Poetry Fellowship, Complete Works III, Cave Canem, Hannah Lowe, Shira Erlichman, Tom Chivers, my mother, my sister and Tabitha. The Austin family who gave me a place to stay in New Orleans, where I finished the manuscript. Malika Booker, Jacob Sam-La Rose, Nick Makoha, Peter Kahn.

Big up Renata, Ruth and all the NHS speech and language therapists I’ve had over the years. Big up Miss Mukasa, Miss Walker and Miss Willis, the English and support teachers at Blanche Neville Deaf School who helped me develop language and a D/deaf identity in the hearing world. I am me because you are you.

The

Perseverance

‘There is no telling what language is

inside the body’

ROBIN COSTE LEWIS

Echo

My ear amps whistle as if singing

to Echo, Goddess of Noise,

the ravelled knot of tongues,

of blaring birds, consonant crumbs

of dull doorbells, sounds swamped

in my misty hearing aid tubes.

Gaudí believed in holy sound

and built a cathedral to contain it,

pulling hearing men from their knees

as though Deafness is a kind of Atheism.

Who would turn down God?

Even though I have not heard

the golden decibel of angels,

I have been living in a noiseless

palace where the doorbell is pulsating

light and I am able to answer.

What?

A word that keeps looking

in mirrors, in love

with its own volume.

What?

I am a one-word question,

a one-man

patience test.

What?

What language

would we speak

without ears?

What?

Is paradise

a world where

I hear everything?

What?

How will my brain

know what to hold

if it has too many arms?

The day I clear out my dead father’s flat,

I throw away boxes of moulding LPs:

Garvey, Malcolm X, Mandela speeches on vinyl.

I find a TDK cassette tape on the shelf.

The smudged green label reads Raymond Speaking.

I play the tape in his vintage cassette player

and hear my two-year-old voice chanting my name, Antrob,

and Dad’s laughter crackling in the background,

not knowing I couldn’t hear the word “bus”

and wouldn’t until I got my hearing aids.

Now I sit here listening to the space of deafness —

Antrob, Antrob, Antrob.

‘And if you don’t catch nothing

then something wrong with your ears —

they been tuned to de wrong frequency.’

KEI MILLER

So maybe I belong to the universe

underwater, where all songs

are smeared wailings for Salacia,

Goddess of Salt Water, healer

of infected ears, which is what the doctor

thought I had, since deafness

did not run in the family

but came from nowhere;

so they syringed olive oil

and salt water, and we all waited

to see what would come out.

And no one knew what I was missing

until a doctor gave me a handful of Lego

and said to put a brick on the table

every time I heard a sound.

After the test I still held enough bricks

in my hand to build a house

and call it my sanctuary,

call it the reason I sat in saintly silence

during my grandfather’s sermons when he preached

The Good News I only heard

; as Babylon’s babbling echoes.

Aunt Beryl Meets Castro

listen listen, you know I

met Castro in Jamaica in

‘77 mi work with

government under

Manley yessir you

should’da seen me up in

mi younger day mi give

Castro flowers

a blue warm warm

welcome to we

and mi know people who

nuh like it who say him

should stay smokin’ in

him bush, our water and

wood nuh want problem

with dat blaze, but Castro,

him understan’ the history

of dem who harm us, who

make the Caribbean a

kind of mix up mix up

pain. Me believe him

come to look us Black

people in the eye and say

we come from the same

madness but most people

nah wan brave no war and

mi understand dem, but

mi also know how we all

swallow different stones

on the same stony path.

Most dem on the Island

hear life in some Queen’s

English voice but I was

tuned to dem real power

lines, I was picking up all

the signals. Some of dem

say, you know too much

yuh go mad, there a fear

of knowledge for the

power it bring and mi

understand dem just

trying to live and cruise

through life like raft

cruise Black River,

Hunderstan’?

My Mother Remembers

serving Robert Plant, cheeky bugger,

tried to haggle my prices down.

I didn’t care about velvet nothing.

I’m just out in snow on a Saturday market morning

trying to make rent and this is it:

when you’re raised poor the world is touched

different, like you have to feel something, know it

with your hand. You need to know what is

worth what to who. I’ve served plonkers

in my time. That singer, Seal, tried to croon

my prices down. I was like, no no, I’m one

missed meal away from misery, mate!

I used to squat in abandoned factories,

go to jumble sales and come home to piece

together this cupboard, filling it with fabrics.

Then I met this wood sculptor, had these tree-trunk

forearms, said, why not go to

Camden Passage on Wednesday?

I had this van, made twenty-eight quid.

Look, everything I sold is listed in this notebook.

Fabrics, cleaned from your Great Gran’s house.

Vintage. People always reach back to times

gone and that’s what I’m saying,

people want to carry the past. Make it

fit them, make it say, this is still us.

I’d take sewn dresses made in the ‘20s.

Your Great Gran was a dressmaker,

you know, dresses carried her. I wore

this white and green thing to

her funeral. Sorry, guess everything

has its time. Are you ready to eat

or am I holding you up?

Jamaican British

after Aaron Samuels

Some people would deny that I’m Jamaican British.

Anglo nose. Hair straight. No way I can be Jamaican British.

They think I say I’m black when I say Jamaican British

but the English boys at school made me choose: Jamaican, British?

Half-caste, half mule, house slave — Jamaican British.

Light skin, straight male, privileged — Jamaican British.

Eat callaloo, plantain, jerk chicken — I’m Jamaican.

British don’t know how to serve our dishes; they enslaved us.

In school I fought a boy in the lunch hall — Jamaican.

At home, told Dad, I hate dem, all dem Jamaicans — I’m British.

He laughed, said, you cannot love sugar and hate your sweetness,

took me straight to Jamaica — passport: British.

Cousins in Kingston called me Jah-English,

proud to have someone in their family — British.

Plantation lineage, World War service, how do I serve Jamaican British?

When knowing how to war is Jamaican British.

Ode to My Hair

When a black woman

with straightened hair

looks at you, says

nothing black about you,

do you rise like wild wheat

or a dark field of frightened strings?

For years I hide you under hats

and, still, cleanly you cling to my scalp,

conceding nothing

when they call you too soft,

too thin for the texture

of your own roots.

Look, the day is yellow Shea butter,

the night is my Jamaican cousin

saying your skin and hair mean

you’re treated better than us,

the clippings of a hot razor

trailing the back of my neck.

Scissor away the voice of the barber

who charges more to cut

this thick tangle of Coolie

now you’ve grown a wildness,

trying to be my father’s ‘fro

to grow him out, to see him again.

The Perseverance

‘Love is the man overstanding’

PETER TOSH

I wait outside THE PERSEVERANCE.

Just popping in here a minute.

I’d heard him say it many times before

like all kids with a drinking father,

watch him disappear

into smoke and laughter.

There is no such thing as too much laughter,

my father says, drinking in THE PERSEVERANCE

until everything disappears —

I’m outside counting minutes,

waiting for the man, my father

to finish his shot and take me home before

it gets dark. We’ve been here before,

no such thing as too much laughter

unless you’re my mother without my father,

working weekends while THE PERSEVERANCE

spits him out for a minute.

He gives me 50p to make me disappear.

50p in my hand, I disappear

like a coin in a parking meter before

the time runs out. How many minutes

will I lose listening to the laughter

spilling from THE PERSEVERANCE

while strangers ask, where is your father?

I stare at the doors and say, my father

is working. Strangers who don’t disappear

but hug me for my perseverance.

Dad said this will be the last time before,

while the TV spilled canned laughter,

us, on the sofa in his council flat, knowing any minute

the yams will boil, any minute,

I will eat again with my father,

who cooks and serves laughter

good as any Jamaican who disappeared

from the Island I tasted before

overstanding our heat and perseverance.

I still hear popping in for a minute, see him disappear.

We lose our fathers before we know it.

I am still outside THE PERSEVERANCE, listening for the laughter.

I Move Through London like a Hotep

What you need will come to you at the right time, says the Tarot card I overturned at my friend Nathalie’s house one evening. I was wondering if she said something worth hearing. What? I’m looking at

her face and trying to read it, not a clue what she said but I’ll just say yeah and hope. Me, Tabitha and her aunt are waffling in Waffle House by the Mississippi River. Tabitha’s aunt is all mumble. She either said do you want a pancake? or you look melancholic. The less I hear the bigger the swamp, so I smile and nod and my head becomes a faint fog horn, a lost river. Why wasn’t I asking her to microphone? When you tell someone you read lips you become a mysterious captain. You watch their brains navigate channels with BSL interpreters in the corner of night-time TV. Sometimes it’s hard to get back the smooth sailing and you go down with the whole conversation. I’m a haze of broken jars, a purple bucket and only I know there’s a hole in it. On Twitter @justnoxy tweets, I can’t watch TV / movies / without subtitles. It’s just too hard to follow. I’m sitting there pretending and it’s just not worth it. I tweet back, you not being able to follow is not your failure and it’s weird, giving the advice you need to someone else, as weird as thinking my American friend said, I move through London like a Hotep when she actually said, I’m used to London life with no sales tax. Deanna (my friend who owns crystals and believes in multiple moons) says I should write about my mishearings, she thinks it’ll make a good book for her bathroom. I am still afraid I have grown up missing too much information. I think about that episode of The Twilight Zone where an old man walks around the city’s bars selling bric-a brac from his suitcase, knowing what people need –– scissors, a leaky pen, a bus ticket, combs. In the scene, music is playing loud, meaning if I were in that bar I would miss the mysticism while the old man’s miracles make the barman say, WOAH, this guy is from another planet!

Sound Machine

‘My mirth can laugh and talk, but cannot sing;

My grief finds harmonies in everything.’

JAMES THOMSON

And what comes out if it isn’t the wires

Dad welds to his homemade sound system,

which I accidently knock loose

while he is recording Talk-Over dubs, killing

the bass, flattening the mood and his muses,

making Dad blow his fuses and beat me.

But it wasn’t my fault; the things he made

could be undone so easily —

The Perseverance

The Perseverance