- Home

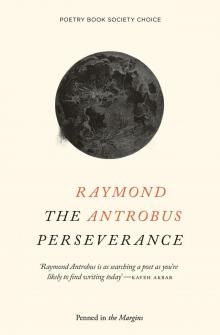

- Raymond Antrobus

The Perseverance Page 2

The Perseverance Read online

Page 2

and we would keep losing connection.

But praise my Dad’s mechanical hands.

Even though he couldn’t fix my deafness

I still channel him. My sound system plays

on Father’s Day in Manor Park Cemetery

where I find his grave, and for the first time

see his middle name, OSBERT, derived from Old English

meaning God and bright. Which may

have been a way to bleach him, darkest

of his five brothers, the only one sent away

from the country to live up-town

with his light skin aunt. She protected him

from police, who didn’t believe he belonged

unless they heard his English,

which was smooth as some up-town roads.

His aunt loved him and taught him

to recite Wordsworth and Coleridge — rhythms

that wouldn’t save him. He would become

Rasta and never tell a soul about the name

that undid his blackness. It is his grave

that tells me the name his black

body, even in death, could not move or mute.

Dear Hearing World

after Danez Smith

I have left Earth in search of sounder orbits,

a solar system where the space between

a star and a planet isn’t empty. I have left

a white beard of noise in my place and many

of you won’t know the difference. We are

indeed the same volume, all of us eventually fade.

I have left Earth in search of an audible God.

I do not trust the sound of yours.

You wouldn’t recognise my grandmother’s Hallelujah

if she had to sign it, you would have made her sit

on her hands and put a ruler in her mouth

as if measuring her distance from holy.

Take your God back, though his songs

are beautiful, they are not loud enough.

I want the fate of Lazarus for every deaf school

you’ve closed, every deaf child whose confidence

has gone to a silent grave, every BSL user

who has seen the annihilation of their language,

I want these ghosts to haunt your tongue-tied hands.

I have left Earth, I am equal parts sick of your

oh, I’m hard of hearing too, just because

you’ve been on an airplane or suffered head colds.

Your voice has always been the loudest sound in a room.

I call you out for refusing to acknowledge

sign language in classrooms, for assessing

deaf students on what they can’t say

instead of what they can, we did not ask to be a part

of the hearing world, I can’t hear my joints crack

but I can feel them. I am sick of sounding out your rules —

you tell me I breathe too loud and it’s rude to make noise

when I eat, sent me to speech therapists, said I was speaking

a language of holes, I was pronouncing what I heard

but your judgment made my syllables disappear,

your magic master trick hearing world — drowning out the quiet,

bursting all speech bubbles in my graphic childhood,

you are glad to benefit from audio supremacy,

I tried, hearing people, I tried to love you, but you laughed

at my deaf grammar, I used commas not full stops

because everything I said kept running away,

I mulled over long paragraphs because I didn’t know

what a natural break sounded like, you erased

what could have always been poetry

You erased what could have always been poetry.

You taught me I was inferior to standard English expression —

I was a broken speaker, you were never a broken interpreter —

taught me my speech was dry for someone who should sound

like they’re underwater. It took years to talk with a straight spine

and mute red marks on the coursework you assigned.

Deaf voices go missing like sound in space

and I have left earth to find them.

‘Deaf School’ by Ted Hughes

The deaf children were monkey nimble, fish tremulous

and sudden.

Their faces were alert and simple

Like faces of little animals, small night lemurs caught in

the flash light.

They lacked a dimension,

They lacked a subtle wavering aura of sound and responses

to sound.

The whole body was removed

From the vibration of air, they lived through the eyes,

The clear simple look, the instant full attention.

Their selves were not woven into a voice

Which was woven into a face

Hearing itself, its own public and audience,

An apparition in camouflage, an assertion in doubt

Their selves were hidden, and their faces looked out of

hiding.

What they spoke with was a machine,

A manipulation of fingers, a control-panel of gestures

Out there in the alien space

Separated from them.

Their unused faces were simple lenses of watchfulness

Simple pools of earnest watchfulness

Their bodies were like their hands

Nimbler than bodies, like the hammers of a piano,

A puppet agility, a simple mechanical action

A blankness of hieroglyph

A stylized lettering

Spelling out approximate signals

While the self looked through, out of the face of simple

concealment

A face not merely deaf, a face in the darkness, a face unaware,

A face that was simply the front skin of the self concealed and

Separate

After Reading ‘Deaf School’ by the Mississippi River

No one wise calls the river unaware or simple pools;

no one wise says it lacks a dimension; no one wise

says its body is removed from the vibration of air.

The river is a quiet breath-taker, gargling mud.

Ted is alert and simple.

Ted lacked a subtle wavering aura of sound

and responses to Sound.

Ted lived through his eyes. But eye the colossal

currents from the bridge. Eye riverboats

ghosting a geography of fog.

Mississippi means Big River, named by French colonisers.

The natives laughed at their arrogant maps,

conquering wind and marking mist.

The mouth of the river laughs. A man in a wetsuit emerges,

pulls misty goggles over his head. Couldn’t see a thing.

He breathes heavily. My face was in darkness.

No one heard him; the river drowned him out.

For Jesula Gelin, Vanessa Previl and Monique Vincent

When three deaf women

were found murdered,

their tongues cut out

for speaking sign language,

the papers called it

a savage ritualistic act —

but I think the world

should have gone silent,

should have heard the deaf

gather at Saint Vincent,

should have heard the quiet

march towards Port-au-Prince.

‘The British government did not recognise British Sign Language until 2002’

BSL ZONE (DEAF HISTORY)

Before, all official languages

were oral. The Deaf were a colony

the hearing world ignored

and now, the irony, that the words noise

and London are the same sign in BSL.

It is getting so loud

au

diologists are preparing

for the deafest generation

in heard history.

In Montego Bay, a sign

written on the outside walls

of the Christian deaf school says

Isiah 29:18 In that day the deaf shall hear

above a painting of a green hill paradise.

Harriott, the only Deaf teacher in the school,

tells me no one speaks sign well enough

to enter any visions of valleys.

My Dad never called me deaf,

even when he saw the audiogram.

He’d say, you’re limited,

so you can turn the TV up.

He didn’t mean to be cruel.

He was thinking about his friend

at school in Jamaica who stabbed

another boy’s eardrums with pencils.

Dad never saw him in class again.

Maybe that’s what he was afraid of;

that the deaf disappear, get carried away

bleeding from their ears.

Conversation with the Art Teacher

(a Translation Attempt)

Shit and good my education. Hearing teachers not see potential. This my confusion life, 90s hearing teachers not think I can become artist because of deafness but funny thing, Deaf girl does GCSE art in six months and go on to get degree. I have proved many wrongs. I am costume designer, teacher, artist. At school I said, “I want to be a costume designer.” Teacher says, “I can’t.” I can’t? So harsh. My father, hearing, signs. Says I can follow dream and lucky me, I did. Proving people wrong is great but tiring. Was I born deaf? You asking lots of questions! OK, yes, in Somaliland, I was about two, meningitis. Seven other children in my hospital ward, all died. My father worked around Europe and took me with him. English hospital saved me. I still know some Somali sign. Wait, you write down what I say, how? You know BSL has no grammar structure? How you write me when I am visual? Me, into fashion, expression in colour. How will someone reading this see my feeling?

The Ghost of Laura Bridgeman Warns Helen Keller About Fame

They’ll forget you, but not

until men have sat close, touched

your hands, asked their questions.

What is divinity? Eternity? Insouciance?

Your name will be scratched into reports

naming you proof that those born

deaf or blind or both are worth

an incapable God, a fragmented sermon.

They will want to know if “intelligence”

has a hand shape. It took one man

called Dickens to open my story

to the world and call it how he saw,

how he heard. Your danger is

in his language. Don’t let them twist

your silence –– the ear and eye

are at the seat of their perception.

We are centuries away from people

believing our stories without

perversion, without pity. Their speech

will never really find a way into us,

will always be the sound

of our separation. Who is testing

God’s hearing when you ask if my blood

is dead? If I am dead, where is my thinking?

Beware of Alexander Graham Bell.

Decibel is his word.

He never receives you. O Helen,

don’t trust what you cannot say yourself.

The Mechanism of Speech*

His tongue was too far forward

His tongue further back

His tongue too high, too low

His incorrect instrument

his difficult power

to muscle

meaning

* Lectures delivered before the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf by Alexander Graham Bell. An erasure.

Doctor Marigold Re-evaluated

‘If a written word can stand for an idea as well as a spoken word can, the same may be said of a signed word’

HARLAN LANE

My BSL teacher taught me about affirmation and negation, saying, in sign: if you are crying and someone asks, “are you crying?” you must answer with a smile and nod to affirm, “yes, crying.”

I thought about Charles Dickens. About everyone laughing and crying in 1843 while he performed Doctor Marigold. The story is of a Cheap Jack trader pushing his cart through east London, who adopts a deaf girl called Sophy after losing his own daughter, because grief never leaves, it just changes shape. Dickens visited deaf schools, interviewed the students before shaping his story.

So let’s love that Sophy and Doctor Marigold invent their own home signs. Let’s love that Sophy goes to a deaf school, learns to read. Let’s laugh when two deaf people fall in love. Let’s laugh when Sophy writes a letter to Doctor Marigold hoping the child is not born deaf. Let’s laugh at the people who hope their child is born with a pretty voice. Let’s speak in the BSL word order — sign you speak? — while celebrating and rolling our eyes at the signature sentimental ending. It’s said that as Dickens read in Whitechapel, hearing people cried in the street when Sophy spoke (an unexplained miracle).

I want my BSL teacher to sign to everyone in 1843, are you crying? I want everyone to smile and nod, yes, crying.

The Shame of Mable Gardiner Hubbards

‘Where in literature are the deaf seen truly, with deafness just one condition of their lives, acting in concert, with deaf and hearing people, not living as isolates?’

LYDIA HUNTLEY SIGOURNEY (poet & teacher, 1814)

I shrink at any reference to my disability,

leave dinner halls with table edge marks in my chest

from hours leaning in. I lock myself in ladies’ rooms

to rest, away from noise, to not be the girl going gah gah.

To pass as normal I rehearse my listening in mirrors.

My lips move and I wait for the right time to nod. A nod

restores my civility. I burned to absorb every decibel.

Look, ladies with perfect responses. A child drops

a spoon and their ears know where it landed.

Breed out our deafness, sterilise the shame of our species.

I love the man who forgets I cannot hear,

who plays piano and recites Shakespeare.

Everything he does shakes the floor; his name is Bell.

Two Guns in the Sky for Daniel Harris

When Daniel Harris stepped out of his car

the policeman was waiting. Gun raised.

I use the past tense though this is irrelevant

in Daniel’s language, which is sign.

Sign has no future or past; it is a present language.

You are never more present than when a gun

is pointed at you. What language says this

if not sign? But the police officer saw hands

waving in the air, fired and Daniel dropped

his hands, his chest bleeding out onto concrete

metres from his home. I am in Breukelen Coffee House

in New York, reading this news on my phone,

when a black policewoman walks in, two guns

on her hips, my friend next to me reading

the comments section: Black Lives Matter.

Now what could we sign or say out loud

when the last word I learned in ASL was alive?

Alive — both thumbs pointing at your lower abdominal,

index fingers pointing up like two guns in the sky.

To Sweeten Bitter

My father had four children

and three sugars in his coffee

and every birthday he bought me

a dictionary which got thicker

and thicker and because his word

is not dead I carry it like sugar

on a silver spoon

up the Mobay hills in Jamaica

past the flaked white walls

of plantation houses<

br />

past canefields and coconut trees

past the new crystal sugar factories.

I ask dictionary why we came here —

it said nourish so I sat with my aunt

on her balcony at the top

of Barnet Heights

and ate salt fish

and sweet potato

and watched women

leading their children

home from school.

As I ate I asked dictionary

what is difficult about love?

It opened on the word grasp

and I looked at my hand

holding this ivory knife

and thought about how hard it was

to accept my father

for who he was

and where he came from

how easy it is now to spill

sugar on the table before

it is poured into my cup.

I Want the Confidence of

Salvador Dali in a 1950s McDonald’s advert,

of red gold and green ties

on shanty town dapper dandies, of Cuba Gooding Jr.

in a strip club shouting SHOW ME THE MONEY,

of the woman on her phone in the quiet coach,

of knowing you’ll be seen and served,

that no one will cross the road when they see you,

the sun shining through the gaps in the buildings,

a glass ceiling in a restaurant

where knives and spoons wink,

a polite pint and a cheeky cigarette, tattoos

on the arms, trains that blur the whole city without delay.

I want the confidence of a coffee bean in the body,

a surface that doesn’t need scratching;

I want to be fluent in confidence so large it speaks from its own sky.

At the airport I want my confidence to board

without investigations, to sit in foreign cafés

without a silver spoon in a teacup clinking

into sunken places, of someone named after a saint,

of Matthew the deaf footballer who couldn’t hear

to pass the ball, but still ran the pitch,

of leather jackets and the teeth

The Perseverance

The Perseverance