- Home

- Raymond Antrobus

The Perseverance Page 3

The Perseverance Read online

Page 3

of hot combs, rollin’ roadmen and rubber.

I don’t want my confidence to lie;

it has to mean helium balloons in any shape or colour,

has to mean rubber tree in rain; make it

my sister leaving home for university, my finally sober father,

my mother becoming a circus clown.

There is such a thing as a key confidently cut

that accepts the locks it doesn’t fit.

Call it a boy busking on the canal path singing

to no one but the bridges

and the black water under them.

After Being Called a Fucking Foreigner in London Fields

Because Dad slapped me

every time I fell into the metal railings

besides the swings, I was the first

in school to cycle without

training wheels. Dad’s style

of discipline didn’t check

for blood, just picked

me up with one hand,

red BMX in the other, his face

a fist, come, come,

pushed me along as I tried

to breathe and balance

the threat of a crash or

punch. A presence I feel in my chest

twenty-five years later walking

on the cycle path in the same park.

I keep my father’s words, violence

is always a failure, so I don’t

swing into the man’s pale

bag-face when he throws

his arms up to fight me.

The truth is I’m not

a fist fighter. I’m all heart,

no technique. Last fought

at sixteen. Broke

two fingers and fractured

my wrist after a bad

swing, my boys bursting to see

a rumble, shouting, breathe breathe breathe,

which is also what my anger

counsellor said when I punched

the wall in her office but seriously —

who gets into fights in their thirties?

Nowadays, instead of violence,

I write until everything goes

quiet. No one can tell me

anything about this radiance.

I’m riding like a boy

on his red BMX — I see myself

turning off the path, racing past

the metal railings, the empty swings.

Closure

Because you stabbed me in the leg in Hackney Community College Library when I was seventeen over a computer, I wonder what else

you would have opened me for?

— — — — — — —— — — — — — —— — — — —

Nike Airs? A Nokia? A hot air balloon ride? Would you have opened me to run towards a Kenyan river?

— — — — — — —— — — — — — —— — — — —

I forgive you for my twenty-one stitches; this scar is how I talk to you.

— — — — — — —— — — — — — —— — — — —

We were boys, we were lost, we were worthy of space. It took me an age to learn there are men in the world who aren’t here to hurt us. There is no knife I want to open you with. Keep all your blood.

— — — — — — —— — — — — — —— — — — —

There is no kingdom to protect, these gates are open. I bring you food. Sit near the leg I couldn’t move after the paramedics stapled it closed, while I pass you a plate of plantain.

— — — — — — —— — — — — — —— — — — —

Laugh when you find out you knew my cousins, or our grandfathers arrived on the same boat, or worked in the same factories, denied the same rooms.

— — — — — — —— — — — — — —— — — — —

Open your ground when we learn that the Jamaican man by the corner shop called us both Little Springs.

Maybe I Could Love a Man

I think to myself,

sitting with cousin Shaun in the Spanish Hotel

eating red snapper and rice and peas as Shaun says,

you talk about your father a lot, but I wasn’t

talking about my father, I was talking about the host

on Smile Jamaica who said to me on live TV,

if you’ve never lived in Jamaica you’re not Jamaican.

I said, my father born here, he brought me back every year

wanting to keep something of his home in me,

and the host sneered. I imagine my father laughing

at all the TVs in heaven. He knew this kind of question,

being gone ten years; people said, you from foreign now.

Cousin Shaun lifts his glass of rum, says, why does anyone

try to change who their fathers are. Later, it is enough

for me to sit with Uncle Barry as he tells me in bravado

about the windows he bricked, thrown out of pubs

for standing ground against the National Front. His name

for my father was ‘Bruck’, because man always ready

to bruck up tings, but I know my Uncle is just trying

to say, I miss him. Look what toughness does

to the men we love, me and Shaun are both trying to hold them.

But if our fathers could see us, sitting

in this hotel, they would laugh, not knowing

what else to do. But I walk away knowing

there are people here that remember my father,

people here who know who I am, who say

our grandfathers used to sit on that hill

and slaughter goats, while our fathers held

babies and their drinks, waving goodbye

to the people on Birch Hill who are and are not us.

Samantha*

What the Devil Said

Some believe I took Samantha’s voice

at the moment she fell on these steps

in her council block, that I snatched

sounds from Samantha’s world

like a collector of voice boxes.

According to her mother

I am like Samantha’s father —

still somewhere behind her daughter,

on her shoulders, in her eyes,

all these years squeezing her dead tongue.

I’ll watch what fires fester.

Look, Samantha knows who I am.

Before her hearing was knocked out

I appeared in tales her mother spun,

taking the form of a spider.

Her mother dreams of webs —

her daughter’s voice held in my cords.

She tries to tear them like wires from walls;

she wails and wails with strain and scripture

but the web is a silk spell that won’t break.

* These poems are based on an interview I conducted with a Deaf Jamaican woman about her arrival in England. I am honoured to have been given permission to write and share her story.

What Samantha Said

Sign is my home, a comfortable home

with only a few rooms I can share.

No one has told my mother the deaf have language.

No one she knows knows how to say this.

She knows fire is a God that won’t stop shouting.

She knows that Job did not charge God for the life he lost.

I know the deaf are not lost

but they are certainly abandoned.

What Samantha’s Mother Said

One night a woman at Bible study asks Samantha’s mother,

why yuh daughter nuh speak, she ghost?

Samantha’s mother swore

this was the moment the Devil’s hand

appeared from behind the book, black and burnt,

covering Samantha’s unmoveable mouth.

The Revivalists

The Revivalists congregate,

speaking in tongues to language

the Devil out of their imaginations.

A preacher in a suit ironed white

approaches the altar.

Staring into the pews, he points

at Samantha’s silence and bellows,

who dare take their ears away from our Lord?

What Samantha’s Father Said

Samantha’s voice never returns but I do.

I see loneliness all over her like measles.

I bought her two rabbits. I mean, who teaches us

more than the beasts of the earth?

I see her sit in her room by the wide window,

stroking their ears, smiling at their twitches.

What Samantha’s Sign Teacher Said

All good words in sign are said with the thumb —

useful, handsome, helpful.

These are the words I give Samantha

when her mother stands in my office shouting,

if the Devil hasn’t got my chile’s voice

you make her speak!

What Samantha Said at the End

We visited my mother after years estranged.

I heard her voice in bits, singing in the hospital.

Morning has bro n like the fi t morning

She had no teeth, her face looked chewed.

Black ird ha poken like the fir bird

She sounded rubbed away

but she still had an organ in her voice.

Pra for the inging

I felt it vibrate under our feet as she hymned.

aise for the morning

She’d forgotten everything except God

and the fact she loves her daughter.

Praise for them pringing fre rom the world.

Dementia had slowly removed

the Devil’s hands from her ears.

Thinking of Dad’s Dick

after Wayne Holloway-Smith

The way it slipped out his trousers

like a horse’s tongue, the way he’d shake it

after pissing, how wide

and long it was. I never thought I’d compete.

Funny to thank him for this now,

how he didn’t really have secrets, was open

about his three children with three different women,

how he ran from them. He told me he’d had sex

with 48 women in his life, said his first week in London

a woman sucked his dick on the top floor of a night bus.

He never held back details. He knew he wouldn’t live

to see me grown. I know that now. He had to give,

while he could, the length of his life to me.

Miami Airport

why didn’t you answer me back there?

you know how loud these things are on my waist?

you don’t look deaf?

can you prove it?

do you know sign language?

I.D.?

why didn’t I see anyone that looked like you

when I was in England?

why were you in Africa?

why don’t you look like a teacher?

who are these photos of?

is this your girlfriend?

why doesn’t she look English?

what was the address you stayed at?

what is the colour

of the bag you checked in?

what was your address again?

is that where we’re going to find dope?

why are you checking your phone?

can I take your fingerprints?

why are your palms sweating?

you always look this lost?

why did you tell me your bag was red?

how did it change colour?

what colour are your eyes?

how much dope will I find in your bag?

why isn’t there dope in your bag?

why did you confuse me?

why did you act strange when there was nothing on you?

would you believe

what I’ve seen in the bags of people like you?

you think you’re going

to go free?

what did you not hear?

His Heart

turned against him in a chicken shop

he said, my heart is falling out

as he slipped into dreams

of his mother in Jamaica

he came through in hospital, longing

for that woman, dead twenty years

his son visits and they spend

half an hour holding hands

there is a needle in his arm

and blood in his colostomy bag

he asks the nurse if he can go to the post office

to buy his daughter a postcard

but forgiveness does not

have an address

Madge is the first girl he kissed in Jamaica

white floral dress, scent of thyme and summer

she visits his hospital dreams

Madge is not the nurse who dissolves

painkillers in his water

he does not drink with his eyes open

his son turns on the radio

it is A Rainy Night In Georgia

his son, a blur

on a wooden chair

Dementia

‘black with widening amnesia’

DEREK WALCOTT

When his sleeping face

was a scrunched tissue,

wet with babbling,

you came, unravelling a joy,

making him euphoric, dribbling

from his mouth —

you simplified a complicated man,

swallowed his past

until your breath was

warm as Caribbean

concrete —

O tender syndrome

steady in his greying eyes,

fading song

in his grand dancehall,

if you must,

do your gentle magic,

but make me unafraid

of what is

disappearing.

Happy Birthday Moon

Dad reads aloud. I follow his finger across the page.

Sometimes his finger moves past words, tracing white space.

He makes the Moon say something new every night

to his deaf son who slurs his speech.

Sometimes his finger moves past words, tracing white space.

Tonight he gives the Moon my name, but I can’t say it,

his deaf son who slurs his speech.

Dad taps the page, says, try again.

Tonight he gives the Moon my name, but I can’t say it.

I say Rain-nan Akabok. He laughs.

Dad taps the page, says, try again,

but I like making him laugh. I say my mistake again.

I say Rain-nan Akabok. He laughs,

says, Raymond you’re something else.

I like making him laugh. I say my mistake again.

Rain-nan Akabok. What else will help us?

He says, Raymond you’re something else.

I’d like to be the Moon, the bear, even the rain.

Rain-nan Akabok, what else will help us

hear each other, really hear each other?

I’d like to be the Moon, the bear, even the rain.

Dad makes the Moon say something new every night

and we hear each other, really hear each other.

As Dad reads aloud, I follow his finger across the page.

NOTES

‘Echo’: Kei Miller’s line appears in his collection, Light Song Of Light (Carcanet, 2010). There is an essay about this poem published on poetryfoundation.org, titled ‘Echo, A Deaf Sequence’. Thanks to Don Share for featuring this poem on The Poetry Magazine Podcast, March 6th 2017.

‘Jamaican British’: Inspired by Aaron Samuels’ poem ‘Broken Ghazal’, in The BreakBeat Poets (Haymarket Books, 2015).

‘The Perseverance’: The Perseverance is the pub on Broadway Market my Dad used to dri

nk in. ‘Love is the man overstanding’ is from Peter Tosh’s ‘Where You Going To Run’ which appears on Mama Africa (EMI, 1983). This poem is a Sestina.

‘I Move Through London Like A Hotep: References The Twilight Zone episode, ‘What You Need’ (season 1, episode 12).

‘Sound Machine’: James Thomson’s line is from ‘Two Sonnets’, originally written in 1730 and reprinted in Don Patterson’s Sonnets 101 (Faber, 2012).

‘Dear Hearing World’: Parts of this poem are riffs and remixes of lines from Dear White America by Danez Smith (Chatto/Greywolf, 2012). Deaf actress Vilma Jackson performs a BSL version of this poem in a short film produced by Adam Docker at Red Earth Studios.

‘Deaf School by Ted Hughes’: Originally published in The Quiet Ear: Deafness in Literature : An Anthology, edited by Brian Grant (Faber, 1988). Hughes admits that this poem was written quickly in his notebook after visiting a deaf school in London.

‘After Reading Deaf School by the Mississippi River’: This poem would not exist without inspiration from Shira Erlichman and the poem ‘The Moon Is Trans’ by Joshua Jennifer Espinoza.

‘For Jesula Gelin, Vanessa Previl and Monique Vincent’: This poem would not exist without the article, ‘Killing of deaf Haitian women highlights community’s vulnerability’ in the Jamaica Observer, which I read while in Kingston visiting family in April 2016.

‘Conversation with the Art Teacher (a Translation Attempt)’: With thanks to Naimo Duale and Oaklodge Deaf School.

‘The Ghost of Laura Bridgeman Warns Helen Keller About Fame’: This poem would not exist without the academic writing of Jennifer Esmail (Reading Victorian Deafness) at the University of Toronto, Gerald Shea (Language Of Light) at Yale University and Laurent Clerc (Autobiography, Gallaudet University, 1817). Laura Bridgeman was a Deaf-Blind student at the Blind Asylum in Boston, who was made famous after Charles Dickens took an interest in her. You can read transcripts in Dickens’ American Notes For General Circulation, Jan – June 1842, in which some of Bridgeman’s answers are lifted and put into this poem.

‘The Mechanism of Speech’: Alexander Graham Bell, famous for inventing the telephone, spent the latter part of his life giving lectures around America and Europe promoting oralism to teachers of the deaf as well as hearing families with deaf children. His lectures were geared towards proving all deaf people could access speech if they are not encouraged to use sign language. He used famous names of his time such as Helen Keller as proof of this, but his case studies were later proved to be either flawed or fraudulent. Interestingly enough, both Bell’s wife and mother were deaf. In Reading Victorian Deafness, Jennifer Esmail says ‘the root of oppression for deaf people is being forced to speak’.

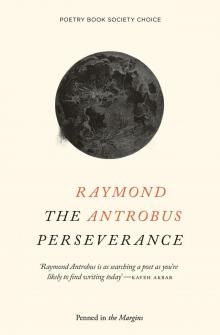

The Perseverance

The Perseverance